Maybe it was the advertising campaign, maybe it’s the nature of a fashion blog-addicted culture, maybe it was a minor eruption of euphoria in the depths of a darkening recession, maybe it was an attempt to shop away memories of the previous night’s Republican debate. Any way you look at it, the launch and liquidation of Target’s Missoni line last Tuesday was unparalleled in both popular excitement and subsequent news coverage and analysis, much of which I consumed in an attempt to make sense of my own enthusiastic yet ambivalent response. (When I write this, understand that even as I seek to examine the affective and political contexts within which I live, think, and dress, I hold myself accountable.)

Of all the rather superficial commentary and outdated theories of class behavior (I’m thinking of you Patt Morrison audience) this observation by marketer AnnaMarie Turano stood out:

“Now that the expensive knitwear’s iconic images (Missoni’s zigzags) are within the reach of the mass audience, Missoni may unfortunately experience backlash from their consumers who were loyal to the brand pre-Target. These Missoni loyalists might stop shopping and might stop wearing Missoni if they are concerned that others might confuse the boutique offerings with the made-for-Target line.”

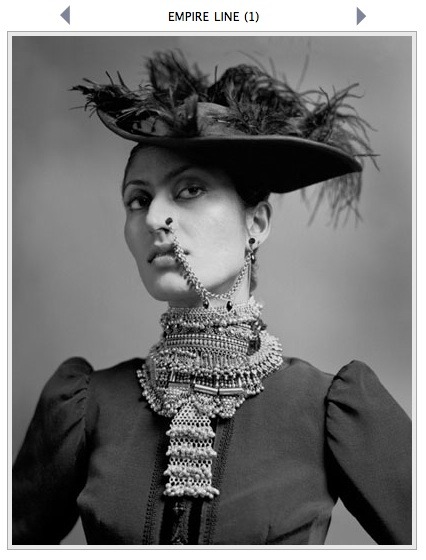

Fashion has a very long history (some would date modern, commercial fashion in the West to as early as the 16th century), one driven by what we would refer to as the class interests of elites to visually display their power and prestige. As sumptuary laws governing the dress of people according to their rank and position faded, and luxurious imports began flowing in from Europe’s growing empire, dress, jewels, and other sartorial practices were utilized to indicate wealth, power, and a studied lack of attachment to the vagaries of the human body. Once the middling classes were able to mimic the crazes of their social superiors, these same superiors found new forms and practices to demonstrate their membership in the vanguard. More interesting, however, is that along with the development of a fledgling fashion discourse and industry, we have the development - erratic, marginal, anarchic, and awesome - of “punk” responses to the consumer identity machine. If the European colonizers perfected the art of using dress as a marker of racial membership and prestige, the colonized excelled at appropriating dress as gestures of challenge, mockery, and then later, outright resistance.

Clearly, the onset of industrialization, and now the technologies of our contemporary age, have sped the fashion cycle so that nearly anything is available in copycat form almost immediately upon its debut on the catwalks of Paris, Milan, and New York. There are entire industries built around the imperative to make high fashion trends available to those who simply cannot or will not spend the time and money necessary to purchase true haute couture. True, these are not punk, in fact they are very much party to the normative bourgeois culture that instantiates class differences and capitalist accumulation while at the same time providing an outlet for participation and the semblance of nose-thumbing, but let me have it, even if for a moment.

So, in response to those commentators who argue that the mass production of high fashion: 1) upsets those who spend money on the “real thing”; and 2) relies on the ignorance and naivete of lower and middle-class consumers who cannot tell the “real thing” from its more cheaply made version I say:

1) The joke’s on you if seeing us makes you rethink your purchase of a “real” Missoni sweater. Our enjoyment in partaking in a little bit of color and design that I refuse to spend any entire month’s pay on has nothing to do with your own enjoyment of the luxury item you have purchased, since they are obviously NOT THE SAME:

2) Nobody believes any more that they are somehow vaulting the social ladder by buying a striped sweater, no matter how cute and colorful it is. The habitus of class are much more complicated than media would have us believe. Dress is not simply a garment that one puts on, but a collection of behaviors, bodily modifications, interpersonal and intertechnological relations, and ways of being that subtly shift our everyday practices as we navigate our way through the myriad and shifting social groupings in which we move.

Additionally, complaining that the Target Missoni craze forebodes the end of our society - as a number of Morrison’s commentators did - because it represents (hysterical) young women’s shift in priorities toward consumerism and away from politics misses the imbrication of these two forces, and also misses the way in which glamour is the texture of our world, the very affective (pre-subjective, emotional) environment in which we move. I think the fashion writer who called into Patt Morrison’s show had it right when she argued that the Missoni line at Target tapped into a cultural zeitgeist - a desire for a little color, fun, and design in the midst of the general awakening of most Americans to the realization that education, hard work, and ambition no longer necessarily lead to wealth, let alone a job that pays a living wage (if it ever did, of course, is something we could discuss).

There was a sense of participating in a communal event to experience pleasure, affinity, and a sense of camaraderie with other like-minded and like-despairing people who cannot afford to spend hundreds or even a thousand dollars on items but refuse to relinquish style nonetheless. This camaraderie, this feeling of pleasure, is not even necessarily something one thinks about in a measured, rational way. Rather it is the opening up of our bodies to our environments. Environments in which color, light, sound, scent, the placement of objects and bodies, technological apparatus, text, all combine to construct spaces of community and subjectification through practices like being in-the-know, sharing this knowledge with others on social media, waking up early to purchase online or head to the local Target, sharing knowing looks and even finds with others, receiving envious looks and scoring a sought-after item, feeling the rush of adrenaline, and creatively incorporating items into one’s extant wardrobe.

Now, a much more measured and thoughtful critique of the hype and frenzy surrounding not just the Missoni launch at Target but the entire project of budget styling would follow through on the comment made by the Women’s Studies professor, Michelle, who called into Patt’s show (the requisite “feminist killjoy” to use Sarah Ahmed’s phrasing and theoretical construction). How is it, she asked, that we are able to purchase clothing and other items so cheaply? What is happening in the invisible process of production and distribution that allows one to buy a Missoni-designed sweater for $29.99 or a Missoni-designed luggage tote for $50? Parsing out the relations among fashionable elites and middle and working-class consumers (with the lens being implicitly focused on the West/Global North) is not enough. Rather, we need to expand our mapping of the relations of production, consumption, and dress to include an examination of relations of power under globalization. Who is making these items? What are the conditions of their labor? Looking at the label and seeing that the luggage was “Made in China” tells us something, but not much. An initial foray into researching the line has led to little information about where the original line was produced, and almost nothing about where and how the Target line was produced so cheaply, besides the obvious: cheaper materials, etc. But what about the people (most likely young women)?

I came home to find out that my prize luggage tote had a Prop 65 warning. “Wash hands after using,” it reminds its potential user. That this potential user might very well be someone utilizing the tote as a diaper bag (as one Target.com reviewer planned to do) is worrisome (I’m returning it). But even more disconcerting, what is the level of lead exposure the people manufacturing the bag (cutting and treating the material, stitching the bag, attaching the handles) are exposed to? What is their relation to, their desires or lack thereof for, the products they make? It is not an accident that information about manufacturers and suppliers is very hard to come by. The difficulty of finding out this information abets the invisibility of labor and allows for the consumer fetishism glamour functions through.

So, what’s the verdict? I don’t think there is an easy one. I do know that it is too easy to simply dismiss participation in such cultural moments, just as it is too easy to ignore the conditions of commodity production. Doing either misses the complexities and mechanics of biopower and globalization as they operate today and relinquishes fashion and culture to those who refuse to take it seriously and/or manipulate it for their own ends.